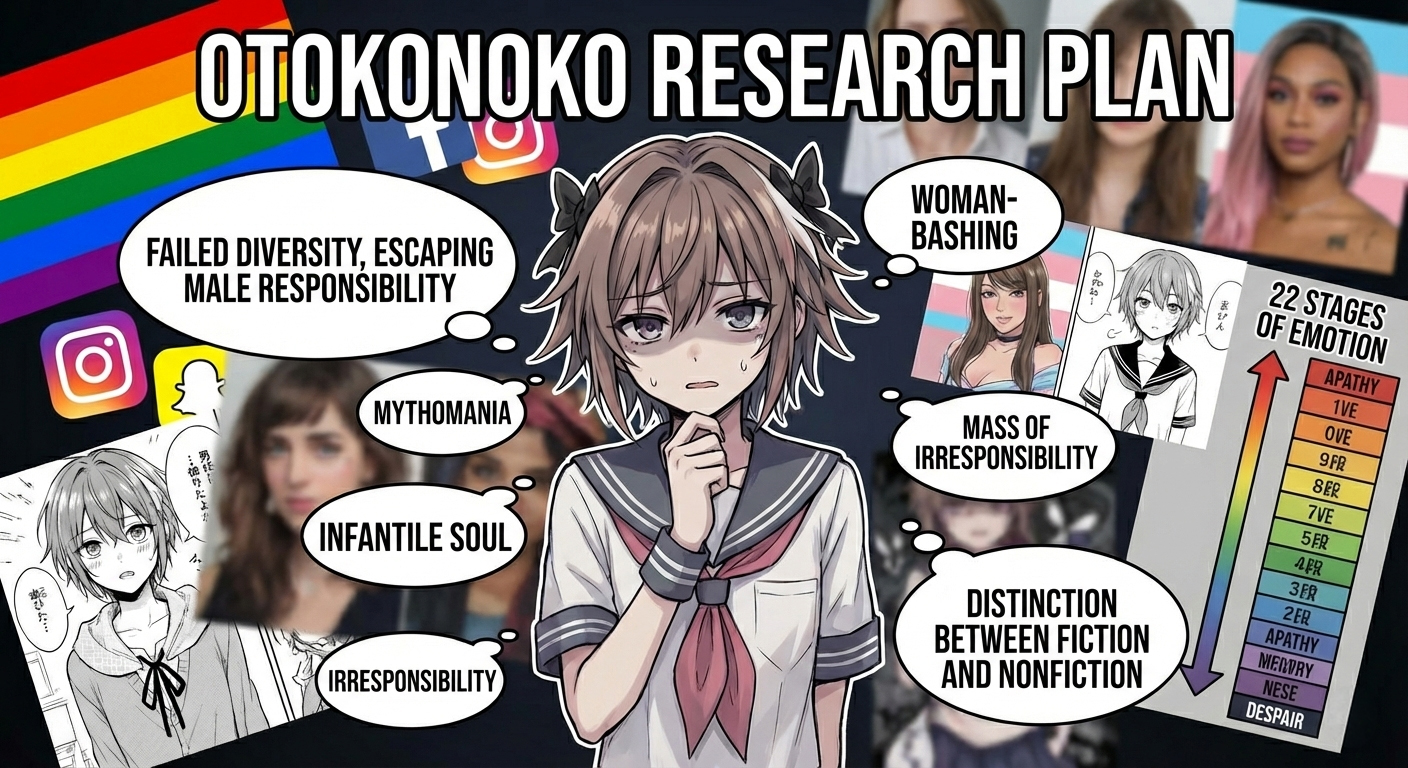

The Collision of Fiction and Reality in “Otokonoko” Culture:

A Psychodynamic Analysis Based on Psychological Responsibility Avoidance, Adult Children Characteristics, and Abraham’s “22 Emotional Stages”

The prayer of transformation revealing anxieties toward maturity and the depths of liminal identity.

- The Multilayered Background of the “Otokonoko” Phenomenon in Postmodern Society

- Cognitive Dissonance and Aesthetic Norms in the Divergence Between Fiction and Reality

- Adult Children (AC) Characteristics and Psychological Responsibility Avoidance

- Analysis of Emotional Dynamics Based on Abraham’s “22 Emotional Stages”

- The Paradox of Misogyny and Maternal Hatred

- Friction with Society and Political Conflict of Gender Identity

- Pathways to Mental Integration: Emotional Navigation and Self-Reeducation

The Multilayered Background of the “Otokonoko” Phenomenon in Postmodern Society

In contemporary Japan, the term “otokonoko” (literally “male daughter”) has transcended mere cross-dressing and gender disruption to establish itself as a robust subcultural identity. This phenomenon — biological males pursuing feminine appearances — originates from the symbolic codification of “cute boys” in two-dimensional media such as animation and manga since the 2000s.

However, as this culture expanded from digital space and social media into the three-dimensional reality, participants have faced severe cognitive dissonance between “idealized fiction” and “inescapable physical and social reality.”

This report examines from multiple perspectives how this divergence burdens individual psychological structures. Specifically, we analyze Adult Children (AC) characteristics formed under the influence of dysfunctional families, psychological dynamics attempting to escape adult male social responsibilities, and emotional transitions using Abraham’s “22 Emotional Stages” scale.

Furthermore, we explore how underlying misogyny (hatred of women) and maternal hatred are sublimated or distorted into the expressive form of “otokonoko,” drawing on theories by Ueno Chizuko and others. The existence of “otokonoko” represents both the forefront of self-expression in a diverse society and a mirror reflecting the spiritual conflicts of modern individuals refusing maturity.

Cognitive Dissonance and Aesthetic Norms in the Divergence Between Fiction and Reality

The Codification of Two-Dimensional Representation and Physical Body Limitations

At the core of “otokonoko” culture lies the illusion of “perfect androgyny” constructed by two-dimensional media. “Otokonoko” in anime and manga are depicted as indistinguishable from females in skeletal structure, voice quality, and skin texture — yet this remains merely a combination of symbols. When actual participants attempt to implement these symbols onto their physical bodies, secondary sexual characteristics as biological males become the greatest barrier.

| Physical Element | Fiction (2D) Characteristics | Reality (3D) Physical Constraints | Psychological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Structure | Delicate shoulders, narrow waist, long limbs | Masculine skeleton, broad shoulders, thick chest | Self-hatred from divergence from ideal |

| Voice Quality | High pitch by female voice actors, neutral tone | Low pitch after voice change, protruding Adam’s apple | Difficulty in social “passing” |

| Skin & Hair | Poreless skin, complete absence of body hair | Blue shadow from shaving, dense body hair, depilation burden | Exhaustion from continuous body maintenance |

| Aging | Perpetual maintenance of “boyishness” | Metabolic decline, masculine aging (hair loss, obesity) | Despair toward future, fixation on time-limited beauty |

As this table demonstrates, fictional “otokonoko” are free from aging and biological constraints, while actual participants face relentless maintenance and the terror of emerging “masculine characteristics” with age. The tendency to depend on excessive plastic surgery, dietary restrictions, and image processing to bridge this gap ultimately perpetuates low-level states (anxiety and powerlessness) in the “22 Emotional Stages” discussed later.

The Coercion of “Effort” and the Stigma of “Failure” in Diverse Society

While the contemporary trend of respecting diversity appears to tolerate liminal beings like “otokonoko,” acceptance actually comes with “aesthetic conditions.” Within society or communities, individuals lacking sufficient “passing degree” (degree of appearing female) or deemed negligent in polishing their appearance are often excluded as “failures” or “uncanny beings.”

This defensive mechanism of “behaving inconspicuously” is intimately connected to Adult Children survival strategies detailed in the next chapter. Particularly in public spaces (toilets, changing rooms, etc.), when appearance is insufficiently “feminine,” it generates anxiety and suspicion in others, which rebounds as attacks or discrimination against the individuals themselves.

Adult Children (AC) Characteristics and Psychological Responsibility Avoidance

Pathological Lying and Construction of the “False Self”

A common psychological background among many individuals oriented toward “otokonoko” is Adult Children (AC) characteristics developed within dysfunctional families. In childhood, ACs acquire the habit of reflexively telling “small lies” to read parental moods and smooth situations. This is a survival strategy against fear of being scolded or to gain attention.

The “otokonoko” identity extends the “false self” employed by ACs — concealing the actual self (oneself as male) and presenting an idealized “cute girlish self.” Their acts of constructing characters on social media using processed images and settings are structurally identical to previously playing “good child” or “mascot (clown)” roles within the family.

| AC Role Typology | Function Within Family | Transfer to “Otokonoko” Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Hero | Shoulders family expectations through excellence | Perfect self-presentation as “charismatic otokonoko” on social media |

| Lost One | Avoids making waves by being inconspicuous, erasing presence | Quietly cross-dressing in society’s margins, escaping from reality |

| Mascot (Clown) | Eases tension by clowning around, creates harmony | Behavior as a “beloved being” or “protected existence” |

| Caretaker | Confirms self-worth by taking care of others | Counsels other participants’ worries, constructs dependent relationships |

Refusal of Maturity and the Dynamics of Responsibility Avoidance

The choice of “otokonoko” has aspects of psychological avoidance behavior against pressures demanded of adult males by society (economic responsibility, family support, maintaining masculinity, etc.). Amid growing criticism of traditional “toxic masculinity,” some men wish to remain in childlike irresponsible positions where being “boys are silly” is laughed off and forgiven.

ACs have low self-esteem and excessively fear failure, tending to avoid new challenges or positions involving responsibility. For them, cross-dressing becomes a means of temporarily departing the “competitive reality” and regressing into “objects” to be protected or admired. This regression phenomenon functions as a kind of mental shelter in the harsh modern society dominated by the principle of self-responsibility.

Analysis of Emotional Dynamics Based on Abraham’s “22 Emotional Stages”

Emotional Scale and Vibrational Discontinuity

Abraham’s “22 Emotional Stages” conceptualizes human emotions as energetic vibrations, hierarchically arranged from Stage 1 (joy, love, gratitude) to Stage 22 (despair, fear, powerlessness). According to this theory, each stage relates to adjacent emotions, and people stabilize emotionally by moving gradually through stages rather than leaping abruptly.

Mapping “otokonoko” participants’ emotional transitions onto this scale reveals their activity cycles violently oscillating between “elation (Stages 1-5)” and “exhaustion/self-loathing (Stages 20-22).”

The Paradoxical Energy Level of Anger and Self-Deprecation

A striking point in Abraham’s teachings is that Stage 16 “anger” has higher energy than Stage 21 “insecurity (self-deprecation).” Many “otokonoko” with AC tendencies are submerged in the swamp of “self-deprecation,” blaming themselves and feeling worthless. To escape this state requires temporarily raising energy by feeling “anger” toward external factors, climbing the emotional ladder.

However, many participants have AC brakes working to be “good children,” suppressing this anger. While techniques like “Process 22” — writing anger on paper or releasing it vocally — are effective, in reality, suppressed anger often transforms into “jealousy (19)” or “revenge (17),” leading to attacks on others through anonymous forums or social media.

Emotion as Navigation for Reality Creation

The 22 Emotional Stages are not merely mood classifications but a navigation system confirming whether one is creating their “desired reality.” If participants feel “freedom (Stage 1)” through cross-dressing, they are in a high vibrational state, becoming a guide attracting positive reality.

However, when based on “expectation (Stage 3)” or “impatience (Stage 12)” premised on others’ approval, it becomes an unstable state easily plummeting to “anxiety (Stage 20)” from slight criticism. To truly raise vibration requires finding “satisfaction (Stage 7)” or “gratitude (Stage 1)” toward one’s current state as-is, rather than fixating on external beauty or ugliness.

The Paradox of Misogyny and Maternal Hatred

Domination and Identification Through Ueno Chizuko’s Misogyny Theory

Analyzing the “otokonoko” phenomenon inevitably confronts underlying misogyny (hatred of women). Ueno Chizuko defines misogyny as “contempt for women among men” and “self-hatred among women.” Male society establishes itself by treating women as “objects of possession (objects of sexual desire or tools for reproduction),” where men must continuously prove they are “not women.”

Yet “otokonoko” deviate from male society’s rules, attempting to identify as “female” themselves. Behind this behavior operate two contradictory psychological mechanisms.

- Appropriation of Femininity

- An attempt to “possess” femininity — supposedly an object of hatred — within oneself, excluding external women and constructing “perfect beauty” self-contained.

- Abandonment of Masculinity

- Escaping into the position of the dominated (object) — women — to flee from fear or hatred of bearing the dominator (possessor) male role.

Maternal Complicity and Internalization of Hatred

“Maternal complicity” refers to mothers’ dual nature — while suffering patriarchal oppression, speaking love to sons yet simultaneously guiding them into the system oppressing themselves. Sons receiving only “conditional love” from mothers in loveless home environments develop deep distrust toward women generally, becoming the root of misogyny.

For men with maternal hatred, cross-dressing sometimes becomes a ritual to “nullify maternal domination.” By destroying the “respectable son” mothers desire while simultaneously becoming “more beautiful and flawless women” than mothers, they exact revenge. However, transformation wishes originating from this “hatred (Stage 18)” cannot fill internal hunger no matter how much appearance is polished, constantly shadowed by “jealousy (Stage 19)” or “anxiety (Stage 20).”

The Chain of “Complications” and Self-Hatred

Just as misogyny among women manifests as “self-hatred,” men desiring feminization also harbor intense self-hatred toward “femininity” within themselves. This is a male version of the structure called “complicated women.”

Manifestation in Male Society

Homophobia: Hatred of homosexuals (maintaining masculinity)

Female Dichotomy: Saint (mother/wife) and whore (sexual object)

Self-hatred: Powerlessness unable to display masculinity

Manifestation in “Otokonoko”

Self-hatred: Intense hatred toward masculine self

Ideal Dichotomy: Ideal 2D beautiful girl vs. ugly real women

Incompleteness: Inability to become a “real woman”

The “femininity” they seek is not “real women” accompanied by physical rawness, daily life atmosphere, and aging — but “beauty as symbol” filtered through fiction. The contradiction of treating real women as objects of “jealousy” or “contempt” while being unable to reach that ideal image themselves further destabilizes participants’ mental states.

Friction with Society and Political Conflict of Gender Identity

Demands for Passing Degree and Resistance to “Toxic Masculinity”

When “otokonoko” venture into society, battles with “weird person” gazes constantly occur. Particularly in contemporary society touting diversity, debates transgender women face in sports and public spaces (toilets, bathrooms, etc.) are not irrelevant to “otokonoko.” Women’s perspectives holding concerns about sexual violence and transgender perspectives receiving discriminatory looks clash intensely.

| Concerns in Public Spaces | Women’s Perspective | “Otokonoko”/Trans Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Toilets / Changing Rooms | Anxiety about physical sexual violence or privacy invasion | Fear of being seen as “weird” and reported |

| Sports Competitions | Doubts about physical ability unfairness | Social alienation and discomfort with debate on “perpetrator’s terms” |

| Daily Interactions | Rejection of “rawness” of masculinity | Powerlessness when “effort” isn’t recognized |

Invisible Terror in Public Spaces

Currently, many “otokonoko” lead daily lives quietly. Behaving inconspicuously without causing anxiety to others becomes their condition for social adaptation. Within this unfair debate, participants constantly feel they are “victims receiving discrimination (Stage 21: powerlessness)” while society views them as “exploiting privileged positions” — a massive perception gap.

Social Reintegration and Escape from Dependence

For “otokonoko” with strong AC tendencies, entering society and working becomes an extremely high hurdle. Among them, many wish for “jobs minimally involving people” or find outlets in “hikikomori (social withdrawal)” or “side businesses (mainly adult-related or social media monetization)” to escape work hardships.

Behind social withdrawal lie deeply involved parent-child relationship problems — “conditional love” from parents and parents unable to trust children. For them to aim for social independence requires first the deep reassurance that “I did nothing wrong (War is over)” and environments permitting them without small lies. However, harsh competitive society rarely grants such grace.

Pathways to Mental Integration: Emotional Navigation and Self-Reeducation

Concrete Processes for Climbing the Emotional Scale

For participants submerged in despair (Stage 22) or anxiety (Stage 20) to “intentionally create” their lives, they must first accurately identify their current position.

- Emotional Identification: When despairing before a mirror, discern whether it’s “powerlessness (21)” or “anger toward one’s own body (16).”

- Discovering Relief Thoughts: Voice or write thoughts providing even slight relief — “I feel ugly now, but makeup skills are improving.”

- Reducing Resistance: Abandon high “resistance” of aiming for perfect femininity; introduce a permission process of aiming for “satisfaction (7)” level today.

Feeling “good” first is the key to attracting desired results (ideal appearance and good relationships). However, this doesn’t mean escapism. Rather, it demands extremely honest self-dialogue — recognizing negative emotions as-is and accepting them.

Overcoming AC and Reconstructing Boundaries

To resolve Adult Children difficulties requires acknowledging past wounds and “reeducating” oneself through process.

- Boundary Awareness: Separate others’ evaluations from self-worth. Understand social media “likes” don’t determine human value.

- Resolving Abandonment Anxiety: Against fear that “being truly known means being hated,” gradually practice revealing authentic self (self-disclosure), accumulating success experiences that lying isn’t necessary.

- Relaxing Perfectionism: Abandon “all-or-nothing” thinking unable to accept anything less than 100 points; permit imperfect self.

Sublation of Fiction and Reality: Avatar Society Prospects

In the future, with metaverse and VR technology proliferation, “avatar selves” separate from physical bodies will carry social weight. For “otokonoko” identity, this could become the definitive technological solution bridging fiction-reality divergence.

However, no matter how technology advances, if “internal consciousness” operating avatars remains captive to past traumas, low self-esteem, and misogyny, new forms of “22 Emotional Stages” decline will repeat there too. True resolution lies not in external transformation but in internal qualitative change — “what to feel and how to connect with others” through transformation.

The Salvation and Limits of “Transformation” in Postmodernity

The fiction-reality divergence in “otokonoko” culture symbolizes not merely appearance issues but “anxieties toward maturity” and “identity uncertainties” modern people harbor. The act of shaving and plastering one’s imperfect body using fiction’s perfect mirror as reference resembles a kind of poignant prayer.

As analyzed in this report, complex psychological dynamics operate behind this — Adult Children survival strategies, avoidance of social responsibilities, and deep-rooted maternal hatred. Yet as Abraham’s “22 Emotional Stages” demonstrate, no matter how deep the abyss of despair, people can use their emotions as navigation, climbing stepwise toward light.

For “otokonoko” choices to become wings building relationships of “love (Stage 1)” for oneself and “satisfaction (Stage 7)” with others — rather than weapons for attacking others or self-destruction — participants themselves need courage to directly face their shadows (misogyny and responsibility-avoidance desires) and integrate them.

Society too should not exclude them as “failures” or “threats” but reconsider problems underlying their life difficulties — “toxic masculinity” and “dysfunctional families” — as shared issues.

The existence of “otokonoko” oscillating between fiction and reality poses fundamental questions to us all: “What does loving oneself as-is truly mean?” Answers to these questions lie not in perfect mirror reflections but only in supple spiritual recovery — forgiving imperfect selves and accepting others’ imperfections too.