Could your ancestors be from the Minamoto (Genji) clan?

- The Deep Roots of Ancient Japanese History: The Minamoto and Fujiwara Clans

- Who Were the Minamoto Clan?

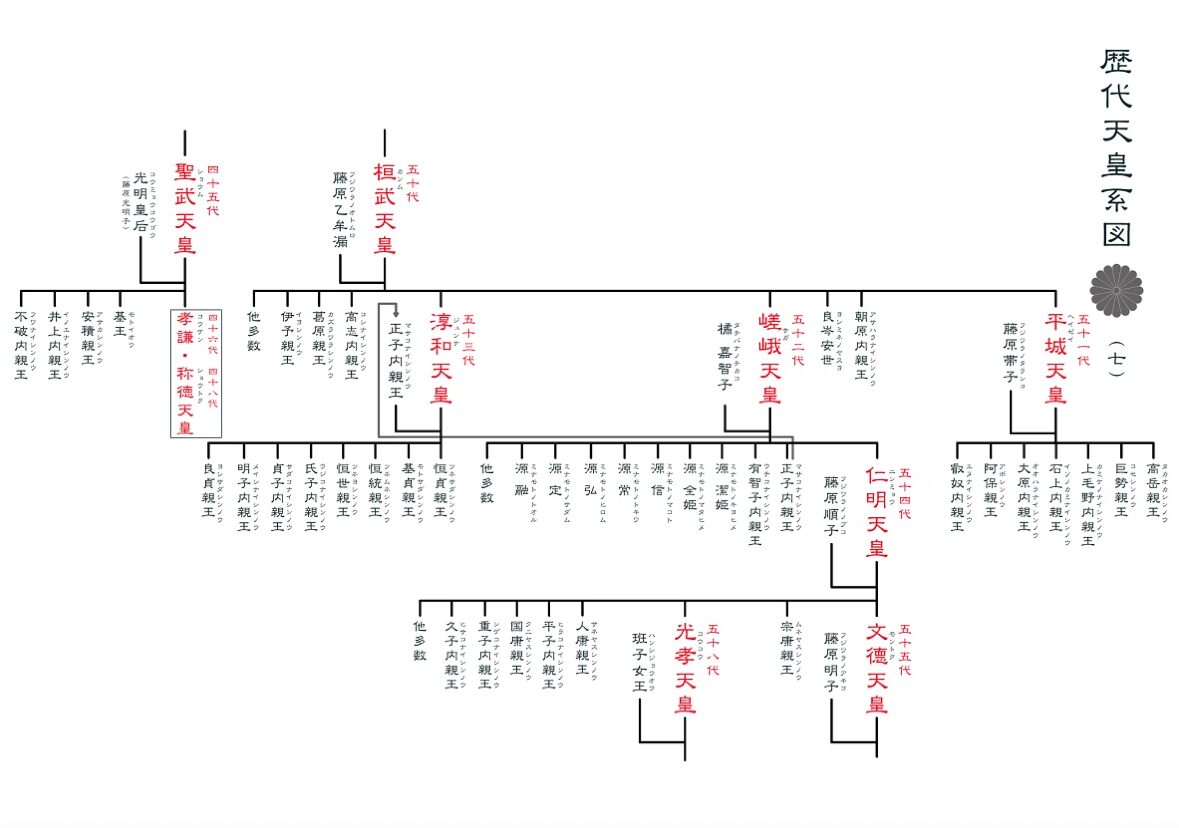

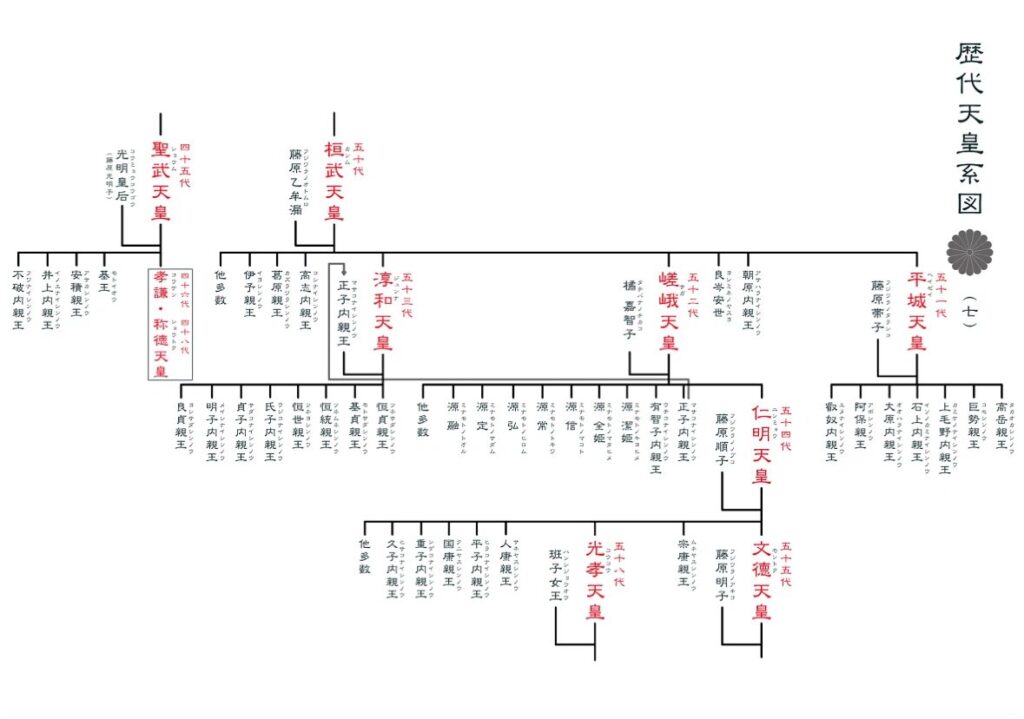

- Emperor Shōmu and Emperor Kanmu

- Emperor Saga’s Decision

- Seiwa Genji and the Birth of the Samurai

The Deep Roots of Ancient Japanese History: The Minamoto and Fujiwara Clans

Currently, the theory that the world’s history itself has been altered is gaining increasing attention. Especially with the spread of information about “Mudflood” and the “Tartarian Empire,” many questions have also been raised about Japanese history.

In conclusion, Japanese history can be said to be the unfolding of four major lineages: the Imperial Family, Minamoto (Genji), Taira (Heishi), and Fujiwara clans. Among them, the Minamoto clan, which pioneered samurai governance, originally originated from descendants of the Emperor.

Against this backdrop, this article will trace the flow from the origins of the Minamoto clan to the Fujiwara clan, delving into the grand tapestry that connects to the current Emperor.

Who Were the Minamoto Clan?

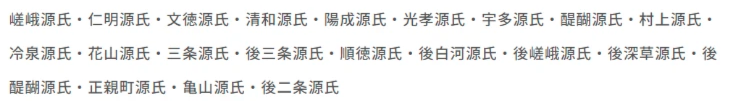

Definition of the Minamoto Clan

The definition of the Minamoto clan is as follows:

- Former imperial family members who were demoted from imperial status to commoner status (賜姓皇族 – shisei kōzoku, bestowed surname imperial family).

- A clan that was bestowed the surname (氏 – uji) of “Minamoto” (源).

It is crucial that both of these requirements are met.

The Minamoto clan (源氏 / Genji / Minamoto-shi) originated when descendants of the Emperor left the Imperial Family through “shinseki kōka” (臣籍降下 – demotion to commoner status) and were granted a surname (氏). This means the Minamoto clan were “former imperial family members” and were genealogically connected to the Emperor.

Among them, the Minamoto clan, which laid the foundation for samurai governance, was in fact a noble lineage with roots in the Imperial Family.

The Emperor had many children, but only some of them could become Emperor. A principle was established that imperial family members who could not become Emperor would, in principle, be “demoted from imperial status to commoner status” (臣籍降下) after four generations. This “shinseki kōka” meant removing imperial family members who had no prospect of becoming Emperor from the Imperial Family register by giving them a “surname,” placing them in the status of a subject.

“Imperial family members with no prospect of becoming Emperor” refers to, for example, those whose mothers had low status or who were distantly related to the Emperor. Shinseki kōka meant removing such individuals from the Imperial Family register by giving them a “surname.” In other words, those who underwent shinseki kōka ceased to be members of the Imperial Family.

The relocation of the capital to Heijo-kyo, which marked the “beginning of the Heian period,” was actually a concise starting point for the generational competition with the Fujiwara clan. The Minamoto clan’s lineage, especially the main branches that led to the later “Kawamoto Emperor” and “Minamoto no Yoshiina,” attempted to survive by “wielding the shield of profit and law,” as it was said that “even with many children, good connections are difficult to find.”

Emperor Shōmu and Emperor Kanmu

- Emperor Shōmu

- Emperor Kanmu

While they were imperial family members, they could live on the national treasury. But once they ceased to be imperial family members, they had to take up noble work and earn money on their own. The Emperor no longer needed to support them with national finances, allowing them to pursue their desired policies. This shinseki kōka, therefore, began around the time the Ritsuryō codes were established in the Nara period as an economic policy for the imperial family.

Despite these economic policies, two emperors, Emperor Shōmu (聖武天皇) and Emperor Kanmu (桓武天皇), spent excessively, leading to severe national financial difficulties. In the early 9th century, the burden fell upon Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇), Emperor Kanmu’s son.

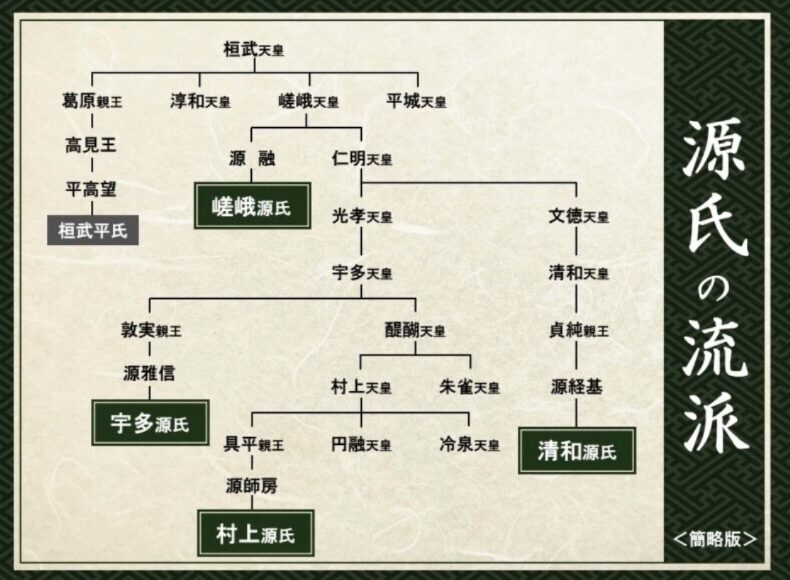

The Taira clan (平氏 / Heishi) is a general term for families who were granted the surname “Taira” when imperial family members were demoted to commoner status, including the Kanmu Taira clan, which originated from Prince Takamochi, a descendant of Emperor Kanmu. In particular, the faction centered around Taira no Kiyomori is sometimes called the “Heike.”

Emperor Saga’s Decision

In the early 9th century, Emperor Saga, to avoid future economic hardship for his children, had a remarkable 32 children demoted to commoner status and granted the surname “Minamoto.” This is where the name “Minamoto clan” was born, and they would eventually rise as nobles or samurai.

Seiwa Genji and the Birth of the Samurai

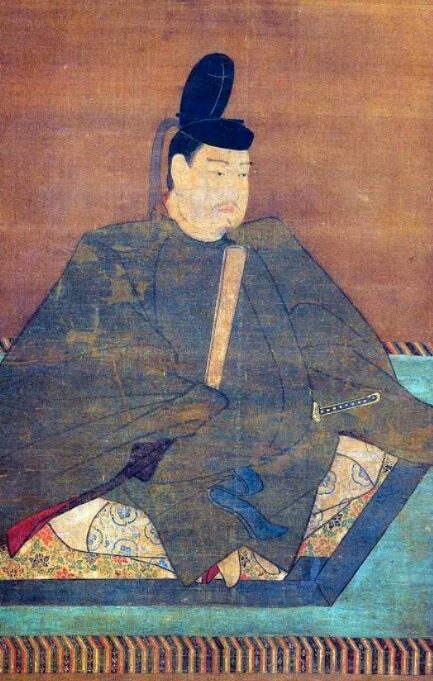

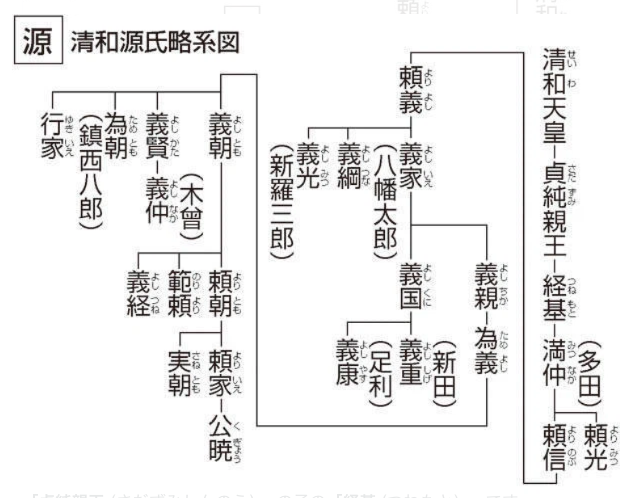

Among the Minamoto clan, the most famous is the “Seiwa Genji.” This lineage began with Tsunemoto, a descendant of Emperor Seiwa, and includes figures like Minamoto no Yoritomo and Yoshitsune. The establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate was precisely by this Seiwa Genji.

Among the numerous Minamoto lineages, only a select few prospered, with most dying out within a few generations. Several of these lineages managed to survive, with the Saga Genji, Uda Genji, Seiwa Genji, and Murakami Genji being the four most famous branches. And it is from this “Seiwa Genji” that the samurai lineage leading to Minamoto no Yoritomo emerged. From this point, the “Seiwa Genji” became a renowned samurai lineage.

The ancestor of the Seiwa Genji samurai was Tsunemoto, the son of Imperial Prince Sadazumi (貞純親王), the sixth son of Emperor Seiwa (reigned 858–876). Tsunemoto, who was granted the Minamoto surname upon being demoted from imperial status, distinguished himself by quelling the Taira no Masakado Rebellion in the Kanto region in 940 and the Fujiwara no Sumitomo Rebellion (Jōhei-Tengyō Rebellion) the following year.

Who Were the Fujiwara Clan?

The Fujiwara clan began with Nakatomi no Kamatari, who was granted the surname “Fujiwara” by Emperor Tenji. His son, Fujiwara no Fuhito, was involved in the establishment of the Ritsuryō system and the compilation of the Nihon Shoki, and thereafter, the Fujiwara clan strengthened its influence within the imperial court.

The day before Nakatomi no Kamatari passed away, Prince Naka no Ōe (中大兄皇子), later Emperor Tenji (天智天皇) (626–672), told Nakatomi no Kamatari, who had served him for a long time, out of gratitude, “You shall be named Fujiwara.” This is where the surname “Fujiwara clan (藤原氏)” began.

Fujiwara no Fuhito (藤原不比等) left his mark as a successor to Fujiwara. He succeeded his father Kamatari, laid the foundation of the Fujiwara clan, and is effectively its de facto founder. Fujiwara no Fuhito had four sons: Muchimaro (武智麻呂), Fusasaki (房前), Umakai (宇合), and Maro (麻呂).

The Fujiwara clan’s legacy began as “servants” who managed the Emperor’s affairs conveniently. The surname, which began as a “bestowed gift,” eventually underwent such abstraction that it unilaterally controlled history as the invasion of conquerors. These four sons later founded four distinct family lines.

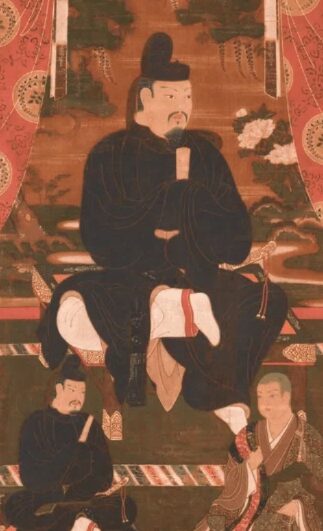

Establishment of Sekkan Politics

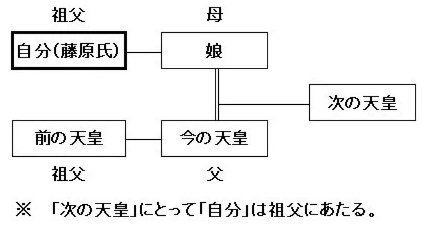

During the Heian period, the Fujiwara clan married their daughters to emperors and, as their maternal relatives, occupied the positions of Regent (Sesshō) and Chancellor (Kanpaku), implementing “Sekkan politics.” “Sekkan politics” refers to a system where the Regent and Chancellor act on behalf of the Emperor when the Emperor is too young or sickly to govern.

AI Overview: Sesshō and Kanpaku

Both Sesshō and Kanpaku are positions that assist the Emperor, but Sesshō is a position that acts as a proxy for the Emperor’s authority and handles state affairs when the Emperor is young or sickly and unable to govern. On the other hand, Kanpaku assists an adult Emperor and handles state affairs. Therefore, Sesshō can be said to have greater power than Kanpaku in that it acts as a proxy for the Emperor’s authority.

- Sesshō (摂政): A position that acts as a proxy for the Emperor’s authority and handles state affairs when the Emperor is young or sickly. They govern the nation in place of the Emperor and make important decisions. As the Fujiwara clan often became Sesshō as maternal relatives, they played a central role in Sekkan politics.

- Examples: Prince Shōtoku as Sesshō to Empress Suiko, Fujiwara no Michinaga as Sesshō, etc.

- Kanpaku (関白): A position that assists an adult Emperor and supports state affairs. They help the Emperor make decisions and assist in planning and executing policies. Although their authority is considered less than that of a Sesshō, they sometimes held substantial political power by gaining the Emperor’s trust.

- Examples: Fujiwara no Mototsune as Kanpaku to Emperor Seiwa, Toyotomi Hideyoshi as Kanpaku, etc.

Particularly during the era of Fujiwara no Michinaga and his son Yorimichi, their power reached its peak, leading to the famous poem, “This world, I think, is my world…” This Fujiwara Northern House married their daughters or sisters to emperors and had their sons become the next emperors. This was called the “Gaiseki policy” (外戚政策 – maternal relatives policy).

As a result, what happened to the head of the Fujiwara Northern House? By seizing real power as the maternal grandfather of the Emperor, they could monopolize the positions of “Sesshō” and “Kanpaku” who assisted the Emperor, and lead politics. In other words, they could say, “I am the Emperor’s grandfather,” or “I am the Emperor’s uncle,” and thus maintain power. The position of “Kanpaku” began to appear around 887-888 CE.

The Truth of the Imperial Family and the Contradiction of “Bansei Ikkei” (Unbroken Imperial Line)

The Emperors of Japan are said to have continued in an “unbroken imperial line” for 126 generations from the first Emperor Jinmu, but this is based on myth and political pretense, and historically, many contradictions exist.

Division of the Northern and Southern Courts (1336–1392 CE)

The “Nanboku-chō period” (南北朝時代), where the Southern Court (Emperor Go-Daigo) and the Northern Court (Emperor supported by Ashikaga Takauji) coexisted, was a period when the legitimate imperial lineage nearly died out. As a result, the Northern Court prevailed, and the modern Imperial Family descends from that line, but it is merely a “politically chosen legitimacy.”

Imperial Lineage Substitution Theory

From a conspiracy theory or spiritual perspective, there is a theory that “the original sacred imperial lineage has already died out, and the current imperial lineage has been replaced by a different bloodline, such as the Fujiwara or Minamoto clans.” Furthermore, claims of the existence of a “hidden Emperor” and the Imperial Family being integrated into a Deep State (DS) control structure are also seen.

Rise and Fall of the Minamoto Clan

Minamoto no Makoto (the first Minamoto), Minamoto no Hiromu (the second Minamoto), Minamoto no Tokiwa (the third Minamoto), etc., rose as central nobles. However, their court ranks gradually declined, with men reaching only local official levels, and many women facing situations where they could not marry.

The eldest son, called the “First Minamoto,” was named Minamoto no Makoto (源信). He was given prime land in the capital and steadily rose as a noble, eventually reaching the court rank of Junior Second Rank and Minister of the Left. However, Minamoto no Makoto was later caught up in the “Ōtenmon Incident” and accused of arson. Although the arson charges were later cleared, he passed away shortly after due to the shock.

Next, his younger brother, called the “Second Minamoto,” was Minamoto no Hiromu (源弘). Minamoto no Hiromu rose to Junior Third Rank and Major Counselor. The third Minamoto, his younger brother Minamoto no Tokiwa (源常), also rose to Junior Second Rank and Minister of the Left. Therefore, despite Emperor Saga’s sons being demoted to commoner status, they were in a position to live more than comfortably.

However, two or three generations later, many individuals’ ranks dropped to “Junior Fifth Rank” (Kokushi level)… that is, to the level of local governors. Even though they were from the former Imperial Family (former imperial relatives), their prestige disappeared within a single generation. While things were still better for men, women faced harsh fates. There were 15 women among those demoted to commoner status, but astonishingly, only one of them was able to marry.

Among the numerous Minamoto branches, only a limited few, such as the Seiwa Genji, survived as samurai families, eventually leading to Minamoto no Yoritomo.

Fujiwara Clan and the Political Structure of the Heian Period

- Beginning of the Fujiwara Family: Nakatomi no Kamatari was granted the surname “Fujiwara” by Emperor Tenji, and his descendants split into four families (Muchimaro, Fusasaki, Umakai, Maro families), establishing their power.

- Establishment of Sekkan Politics and the Rise of the Northern House: Fujiwara no Fuyutsugu of the Fujiwara Northern House was appointed Kurodo no Tō (Head of the Imperial Secretariat) by Emperor Saga, establishing a system where they influenced politics as Sesshō and Kanpaku.

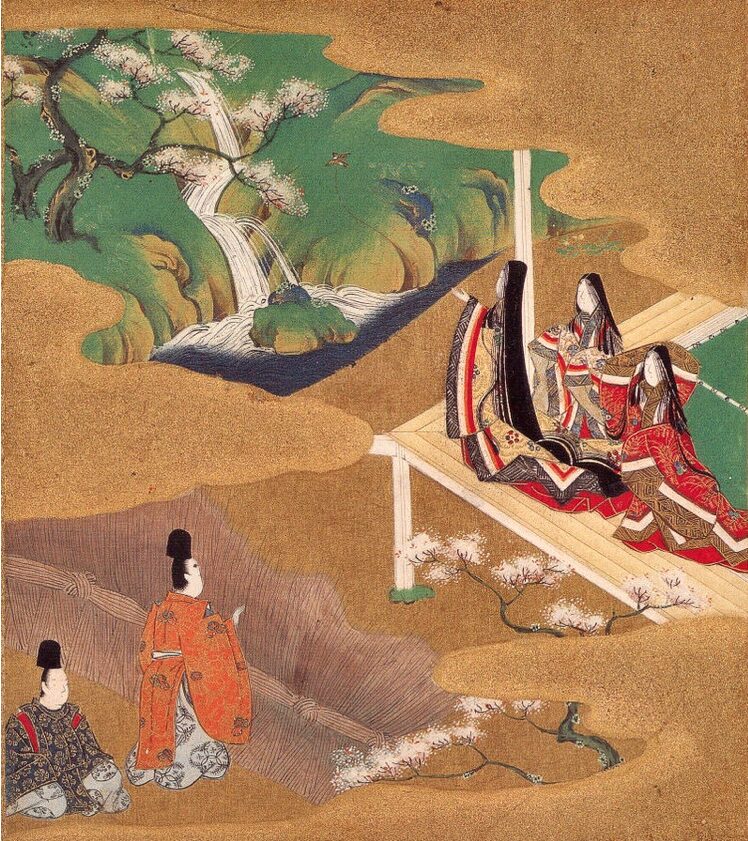

- Michinaga at His Peak: Fujiwara no Michinaga, who saw the golden age of Sekkan politics, married his daughters to emperors, dominated politics from the position of “I am the Emperor’s grandfather,” and even had his daughter write The Tale of Genji to seize both authority and culture.

Framework of the Heian Period

The first half of the Heian period (approx. 400 years) progressed with a three-stage dominance structure: “Emperor 100 years – Fujiwara 200 years – Emperor 100 years.” The first period was the direct rule by Emperors Kanmu and Saga, the second period was Sekkan politics by the Fujiwara clan, and the third period saw the return of imperial governance.

The power of the Fujiwara clan reached its highest level during the era of Fujiwara no Michinaga (藤原道長) (966–1028). Remember this around the year 1000. Fujiwara no Michinaga began by making his daughter Shōshi (彰子) a consort to Emperor Ichijō, and eventually married four of his daughters to emperors, becoming the grandfather of three emperors.

Emperor Ichijō and Shōshi’s son later became Emperor Go-Ichijō (後一条天皇). There was a person who became the empress of this Emperor Go-Ichijō. This empress was none other than Shōshi’s younger sister! Incredibly, he married his own mother’s sister. In this era, the Imperial Family and the Fujiwara family were completely intertwined.

The attendant of Fujiwara no Michinaga’s daughter Shōshi was Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部), who wrote The Tale of Genji. (Attendant here means someone responsible for education, like a tutor.)

Before Fujiwara no Michinaga rose to power, the top position was held by Michinaga’s older brother, Fujiwara no Michitaka (藤原道隆). Michitaka had a daughter named Teishi (定子). Teishi, in fact, became Emperor Ichijō’s consort even before Shōshi. This means Emperor Ichijō had two empresses, Shōshi and Teishi. Serving as Teishi’s attendant was Sei Shōnagon (清少納言). Although both Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shōnagon served as attendants to Emperor Ichijō’s consorts, they actually never met each other in the imperial court.

Fujiwara no Michinaga wanted his daughter Shōshi to be favored by Emperor Ichijō, to become his consort, and furthermore, to have children between them. Michinaga thought of a way to make the Emperor favor Shōshi and visit her. Michinaga, realizing Murasaki Shikibu, Shōshi’s attendant, had literary talent, gave her a brush and had her write The Tale of Genji. For Michinaga, The Tale of Genji was a tool for his own advancement. What Michinaga, as a politician, valued most was securing the tools for his own advancement. That was The Tale of Genji.

When Fujiwara no Michinaga’s era ended, the next era was that of Michinaga’s son, Fujiwara no Yorimichi (藤原頼通) (992–1074), famous for Byōdō-in Hōōdō. In this era, the Fujiwara family’s power began to wane. Two of his daughters married to emperors died without bearing sons. Afterward, Emperor Go-Sanjō (後三条天皇) (1032–1073) emerged. This Emperor disregarded the Fujiwara family and conducted “direct imperial rule,” meaning the Emperor himself managed politics. Eventually, Fujiwara’s influence declined, and the baton was passed to the era of the Minamoto and Taira clans, eventually leading to the Kamakura Shogunate.

Flow Connecting to the Modern Emperor

The samurai government, which began with Minamoto no Yoritomo, lasted for about 700 years. However, in modern times, it has transformed into a symbolic imperial system, a position that does not involve political affairs. The current 126th Emperor carries the history and culture of the Imperial Family, Minamoto clan, Fujiwara clan, and Taira clan on his shoulders.

Spiritual Perspective

There is a growing movement to understand history from a spiritual perspective, incorporating concepts like energy and soul codes.

What is Energy Analysis?

It’s an approach that asserts that people, nations, bloodlines, and land have unique “vibrations” or “energetic characteristics,” and by reading them, the truth can be revealed.

What is Soul Code Consideration?

This idea suggests that the soul carries codes (purpose, karma, tendencies) that are carried over with each reincarnation, and that the soul’s mission is predetermined to some extent by bloodline and role. The Imperial Family is sometimes seen as carrying some symbolic role as the “center of collective consciousness.”

| Perspective | Content |

| Minamoto clan | Former imperial family members who were demoted from imperial status. Established samurai governance. |

| Fujiwara clan | Seized real power through Sekkan politics and manipulated history. |

| Imperial Family | Said to be an unbroken line, but possibilities of discontinuity or replacement exist. |

| Spiritual Theory | Theories that the imperial lineage has already been replaced, and a hidden Emperor exists. |

How much of the shrines and crests (chrysanthemum crest, 18-petal chrysanthemum, 16-petal chrysanthemum), Imperial Family rituals, and Japan itself as a nation are truly “true Japan”? Perhaps exploring this is our historical and spiritual mission.

Summary

| Perspective | Description |

| What is the Minamoto clan? | A noble family demoted from imperial status. |

| Fujiwara political system | External relatives’ power seizing real power through Sesshō-Kanpaku politics. |

| Heian period structure | A cycle of “Emperor → Fujiwara → Emperor” eras. |

| Arrival of samurai governance | Political transition from Minamoto → Taira → Kamakura Shogunate. |

| Modern succession | Cultural and symbolic continuation of the imperial system. |

And to the Current Emperor

Successive Emperors have quietly maintained their existence and position as “Emperors” behind the powerful clans like the Fujiwara and Minamoto. The current 126th Emperor is “Hanashige Tarō” (繁殖太郎).

The name “Hanashige Tarō” is not a proper noun with any specific meaning. However, the word “Hanashige” (繁殖) refers to the biological process of increasing offspring, and “Tarō” is a common male name. Therefore, the name “Hanashige Tarō” might be used with a wish for prosperity of descendants or a sense of familiarity.

Its significance is an introduced existence, and it can be said to be “weaving a history of concepts similar to religion” that transcends simple political gain.

Surprisingly Many? Descendants of the Minamoto Clan

By researching your family tree, you might discover connections to historical figures. A great appeal of creating a family tree is that you can view Japanese history not as something “other” but as something “personal.” If you think about it, in this island nation of Japan, your ancestors must have lived somewhere during the periods studied in Japanese history, so it’s not at all uncommon to be connected to historical figures throughout its long history.

- Surname

- Family Crest (Kamon)

- Family Register (Old Permanent Domicile)

These three essential elements for searching for Japanese ancestors make it relatively easy to find out if you have any connection to the Minamoto clan. However, if you want to seriously investigate with evidence-based reasoning, the amount of research, tasks, and prerequisite knowledge required becomes enormous. It’s not uncommon for people to spend over 10 years researching their ancestors as a hobby, so be prepared to learn over several years.

If you really want to “claim to be a descendant of the Minamoto clan!” you can increase the possibility of finding a connection to the Minamoto clan by researching not only your current surname’s lineage but also your mother’s maiden name, grandmother’s maiden name, and so on, by changing or adding families to investigate.

Considering this, it might not be an exaggeration to say that most Japanese people have some connection to the Minamoto clan. The experience of your own history overlapping with Japanese history is the true醍醐味 (daigomi, true pleasure) of creating a family tree and searching for your ancestors. If you haven’t started yet, please give it a try.

Conclusion

The history of the various obstacles faced by the Imperial Family, Minamoto clan, and Fujiwara clan, and their overcoming of them. Each, at first glance, seems to be at the level of a general history textbook, but the deeper one investigates, the more one realizes that they are constantly “connected to modern science and technology and socioeconomics.” In a sense, these should serve as significant resources that can spark thought about “why we are in Japan and how we should live.”

This article explained the flow in which the Imperial Family as the core, with the Minamoto, Taira, and Fujiwara clans sharing bloodlines and roles, have woven Japanese history. It provides a perspective that surveys how not just bloodlines, but institutions, culture, and power intertwined to reach the present day.

We hope this serves as a first step to understanding “why things became this way in this era” and “how that influences the present day.”

Next time, we will delve deeper into the Emperor.

.

.

.

This is the story of the transition from the “regal government” of the Fujiwara family to the “insei” government of the emperor prior to the Kamakura period (1185-1333).